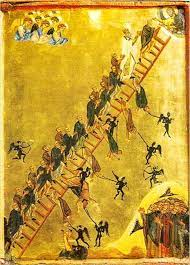

With Lent coming, we are leaving Philokalia for a while to re-read the Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus.

With the exception of the Bible, writes Bishop Kallistos Ware in the introduction of this book, there is no other book as influential and foundational for Orthodox spirituality as the Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus.

While addressed to monastics, it embodies the transformational journey that all Christians are capable of, and have a right to, from the tumult of passions and fragmentation to wholeness, inner stillness and unity with God.

We use the edition, translated by Colm Luibheid and Norman Russell. Note, however, that my quotes are from a different, online translation.

You can order the book from Amazon.

STEP ONE

Like all journeys, the Ladder of Divine Ascent consists of many steps. St. John divides our journey into 30 small steps, which he describes and helps us climb one-by-one.

With his help we travel gradually from detachment and renunciation to the acquisition of fundamental virtues, the struggle against passions and finally the cultivation of dispassion and acquisition of inner stillness. When we reach at the top of the summit, we can directly experience the love of God and become God-like.

The first step, before our real climb even begins, is renunciation of the material world as we know it: our dependence on things, indulgences, addictions to passions, assumptions that close our hearts and minds.

Those who enter this contest must renounce all things, despise all things, deride all things, and shake off all things, that they may lay a firm foundation.

St. John’s audience, of course, is other monks who have chosen to leave the world and live a life of prayer. Yet renunciation is not negation but purification. Its three pillars according to St. John are “innocence, fasting and temperance.” They do not describe a simple deficit but the shedding of artifice and the return to a child-like nature:

Let all babes in Christ begin with these virtues, taking as their model the natural babes. For you never find in them anything sly or deceitful. They have no insatiate appetite, no insatiable stomach, not a body on fire…

Hence the return to a child-like state, free from passions and anxiety is possible for all of us.

Why would a citizen of the 21st century want to deprive himself/herself in an age when self-gratification and actualization are inalienable rights? In the hesychastic (and more broadly, Christian) worldview, material gratification and abandon in passions result in slavery of the soul. Renunciation, on the other hand, paradoxically leads to freedom.

The book’s preface quotes St. Augustine as he puts forth a vision of a life in which we are in union with God.

Imagine a man in whom the tumult of the flesh goes silent, in whom the images of earth, of water, of air and of the skies cease to resound. His soul turns quiet and, self-reflecting no longer, it transcends itself. Dreams and visions end. SO too does all speech and every gesture, everything in fact which comes to be only to pass away. All these things cry out: “We did not make ourselves. It is the Eternal One who made us.”

This is the vision that makes the journey worthwhile.

Unlike other meditative traditions, the journey up the ladder is enabled by faith and love. Why would you even want to undertake such a challenging journey without this motivation, John asks?

5. All who have willingly left the things of the world, have certainly done so either for the sake of the future Kingdom, or because of the multitude of their sins, or for love of God. If they were not moved by any of these reasons their withdrawal from the world was unreasonable. But God who sets our contests waits to see what the end of our course will be.

Our journey is not a willful adventure but a disciplined process that can only be undertaken under the guidance of a spiritual father. This journey, hence, should be driven by humility rather than certainty in our own knowledge and abilities.

In the patristic mindset, life is a constant spiritual warfare and the forces of evil and darkness are real and ever present.

We have very evil and dangerous, cunning, unscrupulous foes, who hold fire in their hands and try to burn the temple of God with the flame that is in it. These foes are strong; they never sleep; they are incorporeal and invisible.

The hope for Christians is that “God belongs to all free beings. He is the life of all, the salvation of all—faithful and unfaithful, just and unjust, pious and impious, passionate and dispassionate, monks and seculars, wise and simple, healthy and sick, young and old—just as the diffusion of light, the sight of the sun, and the changes of the weather are for all alike; ‘for there is no respect of persons with God’”. Being God-lie, then, is our heritage to reclaim.

In hesychasm there is a need for direct and personal experience with God. Only through renunciation can we hear God speak to us directly without intermediaries. Renunciation opens the door to the journey of direct communion with Him.

So that we can hear his word, not in the language of the flesh, not through the speech of an angel, not by way of a rattling cloud or a mysterious parable. But Himself. The One Whom we love in everything.

.