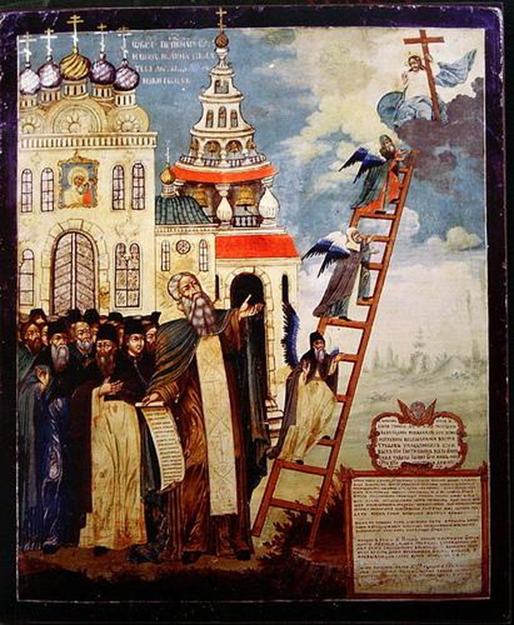

Acquiring virtues, rung by rung in the Ladder, is not a simple, linear act. In this chapter, John explores the complexity of virtues; the thin and changeable boundaries that sometimes barely distinguish them from passions. We have reached a higher level of spiritual growth at this stage that requires more than fighting passions—the understanding of the nuances of truth and the ability to clarify even the subtlest shades of ambiguity. This is why discernment, in addition to hard labor, is necessary at this rung of the Ladder. John highlights some of ambiguities and nuances of situations we should be aware of.

For one thing, the struggle for spiritual ascent is not uniform. John recognizes that virtues like silence, humility and temperance may come easily to some personalities while others have to struggle against their own natures to achieve them. Because the latter clearly have to work harder, John (somewhat reluctantly) considers their achievement to be a little higher than the others’.

Another complexity is that virtue is often mingled with malice and requires discernment and alertness to detect the dividing line between them. Love may conceal lust; hospitality, gluttony; discernment, cunning manipulation of a situation; hope, laziness; tranquility, despondency. To make this message clearer, John likens it to drawing water from a well and accidentally bringing up a frog with it.

Over-achievement of virtues or pursuing them to earn praise is a grave danger that is no different from the soul-destroying addictions of our own times–obsession with achievement and professional status; addictions to ambitions that turn us into workaholics; and lives spinning out of control by stretching our budgets, habits or expectations beyond what we can afford or deliver, plunging us into constant anxiety, fear and, eventually, despair.

John probes even more deeply into the risks of delusion and calls for extraordinary and finely hewn ability for discernment. “Monks should spare no effort in becoming a shining example in all things,” he states. Yet even when reaching for heaven we may be in danger of spreading ourselves too thinly, and “have our wretched souls be pulled in all directions, to take on, alone, a fight against a thousand upon thousands and ten thousands upon ten thousands of enemies, since the understanding of their evil workings, indeed even the listing of them, is beyond our capacities.” I can’t imagine a more accurate description of men and women in our time–the modern professional, driven executive or ambitious soccer mom with a management agenda for her children’s lives. The alternative is to discern God’s will for the right balance. “Instead, let us marshal the Holy Trinity to help us” John advises. Yet it takes humility to give us the discernment to acknowledge the reality of our limitation and need for God’s help. And it takes patience to discern God’s will:

Discernment will also help us make a crucially important distinction—that between God’s will and timing and delusion and false timing, forced by our own will. “If God, who made dry land out of the sea for the Israelites to cross, dwells within us, then the Israel within us, the mind that looks to God, will surely make a safe crossing of this sea…” And John adds: if God “has not yet arrived in us, who will understand the roaring of the waves, that is, of our bodies? Let’s pray for God to dwell in us and for humility to discern his will.