Philokalia, vol. 2, St Theognostos, paragraphs #24-29

I must admit that I think of afterlife as an abstraction, separate from my life as is. St. Theognostos connects the two, on a gritty, experiential level, as he focuses us on the moments of transition from present to eternal life.

He points out that we are especially vulnerable during these moments.

When the soul leaves the body, the enemy advances to attack it, fiercely reviling it and accusing it of its sins in a harsh and terrifying manner.

We cannot face this transition unprepared. This means that, in addition to our preparation for afterlife, we must also arm ourselves with practical weaponry for this very moment of transition.

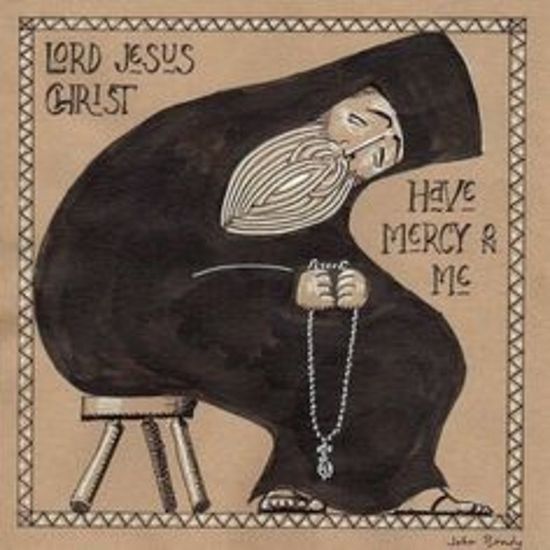

Theognostos zeroes in on this moment, giving instructions and advice with the practical, thorough, matter-of-fact air you would expect to find in a sophisticated travel guide or self-help book. To prepare for our journey, Theognostos advises:

Ask for assurance of salvation, but not too long before your death lest “you should delude yourself into believing that you possess such assurance only to find, when the time comes, that you have failed to attain it.

He gives us encouragement for the journey:

The devout soul, however, even though in the past it has often been wounded by sin, is not frightened by the enemy’s attacks and threats.

He continues with a blueprint for action outlining specific instructions for what to say and do at that time.

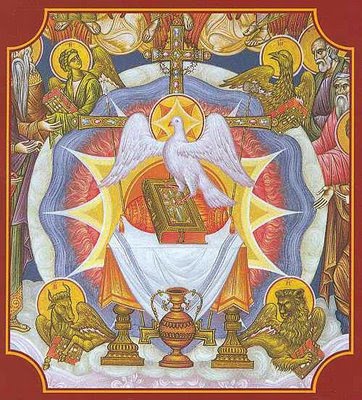

First, we must take courage, remembering that we are “strengthened by the Lord, winged by joy, filled with courage by the holy angels that guide it, and encircled and protected by the light of faith…”

Though our inclination may be to be intimidated and flee, Theognostos tells us to do the opposite—shed our fears and go on the offensive. Instead of shrinking in terror, we should be unafraid to confront the forces of evil with “great boldness.”

The poet Dylan Thomas encourages to “talk back” to the forces of darkness:

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Thomas rages at the human condition that makes us subjects to decay and death, wishing for earthly immortality. Theognostos accepts earthly life as temporary and longs for the peace and joy of the life beyond, in Christ’s presence.

Instead of raging at God, he directs our rage to the dark forces preventing us from entering heaven, through words such as:

Fugitive from heaven, wicked slave, what have I to do with you? You have no authority over me; Christ the Son of God has authority over me and over all things. Against Him have I sinned, before Him shall I stand on trial, having His Precious Cross as a sure pledge of His saving love towards me. Flee from me, destroyer! You have nothing to do with the servants of Christ.

He gives us hope by enabling us to confront the devil and showing us that it is possible to defeat him:

When the soul says all this fearlessly, the devil turns his back, howling aloud and unable to withstand the name of Christ. Then the soul swoops down on the devil from above, attacking him like a hawk attacking a crow. After this it is brought rejoicing by the holy angels to the place appointed for it i n accordance with its inward state.

To transition peacefully from this life to the next, requires inner peace which, in turn, requires detachment from passions. Theognostos tells us that when we are “shackled by an attachment to earthly things,” we are “like an eagle caught in a trap by its claw and prevented from flying.”

Even when you believe that you have battled passions successfully and have achieved a degree of peace, you may be still deluded:

for your soul may still bear within it the imprint of the passions, and so you will have difficulties when you die.

Yet this process of purification takes on a different sense of urgency and concreteness when Theognostos makes us envision our process of transition from this life to the next in minute detail.

This is not simply meditating to achieve a temporary state of serenity on a yoga mat, but a “practical” necessity for achieving the peace that comes from detachment and love before the real moment of transitioning.

For changeless dispassion in its highest form is found only in those who have attained perfect love, have been lifted above sensory things through unceasing contemplation, and have transcended the body through humility.