(Philokalia Vol. III, G.E.H Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware)

We are born, St. Petter writes, with an innate spiritual knowledge which we later lose through passions.

What is the meaning of spiritual knowledge then?

It is the ability to see things as they really are in nature, to uncover the mystery that lies beyond appearance and physical attributes.

The intellect then sees things as they are by nature ….by others it is called spiritual insight, since he who possesses it knows something at least of the hidden mysteries- that is, of God’s purpose- in the Holy Scriptures and in every created thing.

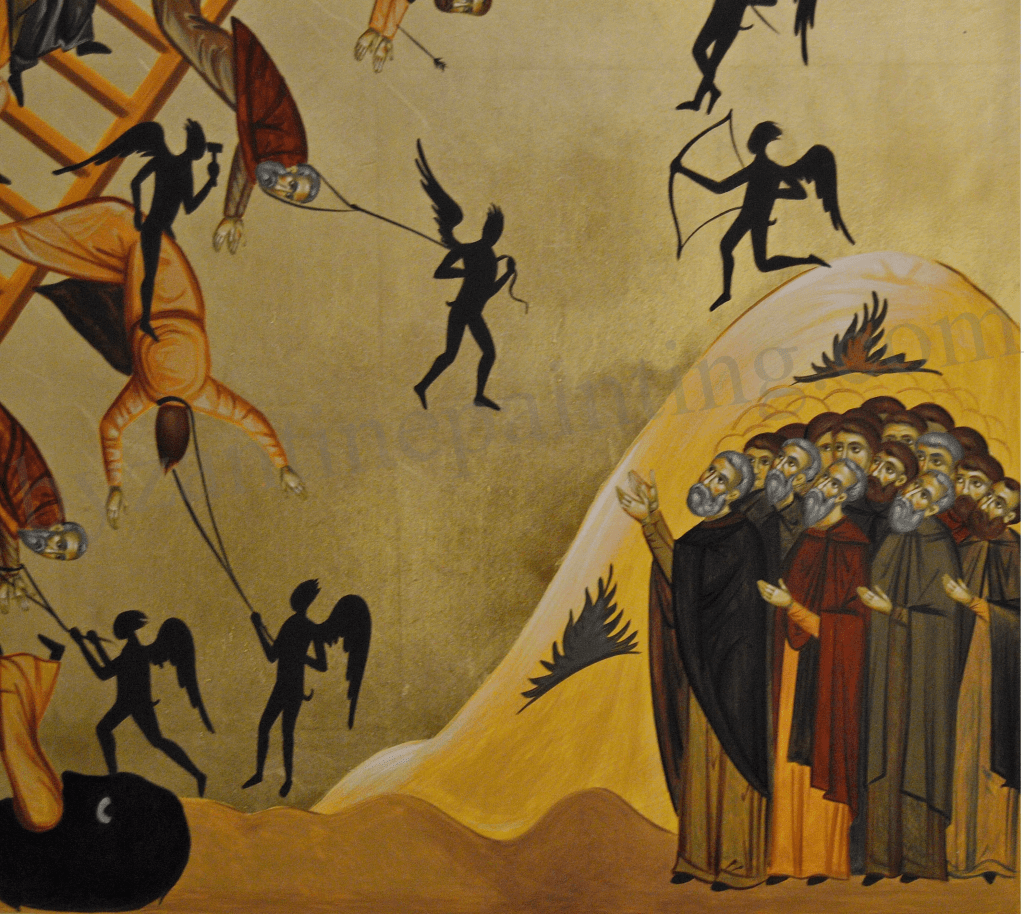

Passions, however, “darken the intellect” and confine us to the surface of things.

Living on the surface is easily exhaustible. We burn through material things, praise, career milestones etc., rapidly. We are, thus, on a frantic course of constantly replenishing the supply and yet, for many of us, a sense of emptiness remains.

The Greeks had an extraordinary understanding of the physical and intellectual realm, we are told, yet they lacked spiritual knowledge, defined here as the discernment of purpose.

Without understanding purpose, one cannot penetrate the true meaning of all things.

…for the pagan Greeks perceived many things but, as St Basil the Great has said, they were unable to discern God’s purpose in created beings, or even God Himself, since they lacked the humility and the faith of Abraham.

Viewed through the lens of spiritual insight, then, nothing is insignificant and worthless. Nothing is dismissible. Nothing is empty. Even a crumb of bread or a boring daily routine points to a larger meaning and purpose.

(God’s purpose) is clearly revealed in the world to come, when everything hidden is disclosed.

A significant difference between Christian and other types of meditative traditions is that the true meaning of things cannot be deciphered through our own resources and will not be revealed without faith.

The gnostic ought not to rely in any way on his own thoughts, but should always seek to confirm them in the light of divine Scripture or of the nature of things themselves. Without such confirmation, there can be no true spiritual knowledge, but only wickedness and delusion.

God and his purpose are there to be discovered—ensconced in simple and lofty things alike, in humble daily discourse and scriptural writings. All we have to do is rid ourselves of passions, assumptions and obsession with our self-interest so we can be filled with spiritual knowledge and allow for the revelation to occur.

We have all seen little children’s wonder-filled eyes as they explore the world with hope, faith and awe. Everything is new, sacred, and filled with unending mysteries and delights. Even a speck of dust is a source of wonder and reveals to them something about a vast and unknown world. This is the state of innocence we must achieve in order to be filled with spiritual knowledge.

Peter expounds on the meaning of faith. It is, he says, going beyond the visible to extrapolate the invisible.

A person is said to have faith when, on the basis of what he can see, he believes in what he cannot see.

Yet, discerning hidden mysteries is not enough if you lack faith in their creator. “But to believe in what we can see of God’s works is not the same as to believe in Him who teaches and proclaims the truth to us.”

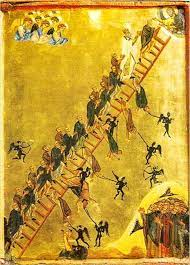

Faith must proceed from the head to the heart. According to St. St. Peter, it is through suffering that one acquires faith, then fear, then awe, then gratitude and humility and, finally, true spiritual knowledge.

In this way, the person who in faith endures these trials patiently will discover, once they have passed, that he has acquired spiritual knowledge, through which he knows things previously unknown to him, and that blessings have been bestowed on him. As a result, he gains humility together with love both towards God, as his benefactor, and towards his fellow-men for the healing wrought by God through them.