Philokalia, vol. 4, On the Inner Nature of Things and on the Purification of the Intellect:

Nikitas Stithatos paints a lyrical image of the state of theosis, that is, union with God:

“When you have reached this state, you enter the peace of the Spirit that transcends every dauntless intellect (cf.Phil. 4 : 7) and through love you are united to God.”

Getting there, however, is not a linear path.

Pride for your spiritual achievements, for example, often creeps in, disrupting contemplation. The tranquility you achieved is shaken as you slip back into wanting to control, draw conclusions and make presumptions on your own. Such self-centered state of mind prevents you from seeing the inner nature of all things through God’s eyes.

Stithatos makes clear that nothing remains static in this process of spiritual ascendance, including the role of the penitent.

“God does not want us always to be humiliated by the passions and to be hunted down by them like hares, making Him alone our rock and refuge (cf. Ps. 1 04 : 1 8);”

God, then, wants us to be in a cooperative relationship with him.

Accordingly, simply resisting the passions is not enough for salvation. Nikitas Stithatos’s emphasis is on the transformation of passions into virtuous energies (rather than their mere annihilation).

To better illustrate this point, he brings up the metaphor of a deer eating snakes (don’t look for scientific evidence here).

“But He wants us to run as deer on the high mountains of His commandments (cf. Ps. 1 04 : 1 8. LXX), thirsting for the life creating waters of the Spirit ( cf. Ps. 42 : 1 ). For, they say, it is the deer’s nature to eat snakes; but by virtue of the heat they generate through being always on the move, they strangely transform the snakes’ poison into musk and it does them no harm. In a similar manner, when passion-imbued thoughts invade our mind, we should bring them into subjection through our ardent pursuit of God’s commandments and the power of the Spirit, and so transform them into the fragrant and salutary practice of virtue. In this way we can take every thought captive and make it obey Christ ( cf. 2 Cor. 1 o : 5).”

The spiritual application follows the deer analogy:

The Process of Transformation given by Stithatos

- Invasion of Thoughts: “Passion-imbued thoughts” will inevitably enter the mind [1]. The goal is not necessarily to avoid these thoughts entirely, but to actively confront them.

- Active Subjection: Through “ardent pursuit of God’s commandments and the power of the Spirit,” the negative thoughts are engaged and brought “into subjection” [1].

- Spiritual Alchemy: The “poison” of the passion is not just neutralized; it is “transformed them into the fragrant and salutary practice of virtue” [1]. The energy of the passion, when channeled correctly through spiritual discipline, becomes something positive and holy (musk).

Free will, then, is not passive but has agency of its own to discern, edit, re-direct and transform.

This “dynamic path” is a key feature of the broader Eastern Orthodox concept of theosis, which involves a synergistic process of human effort and divine grace.

The state of passivity or action, surface or depth depends on the level of engagement we have with God.

Simply disciplining the body is not sufficient for achieving theosis. It is literal and one-dimensional. Yet, “we are meant for more than we can literally imagine,” writes Stithatos. Remaining on the surface–Christians in name only– means that we are simply treading water and we will experience no progress:

“A person who keeps turning round and round on the same spot and does not want to make any spiritual progress is like a mule that walks round and round a well-head operating a water-wheel.”

Becoming one with God in every way is not achieved simply by adhering to technical details.

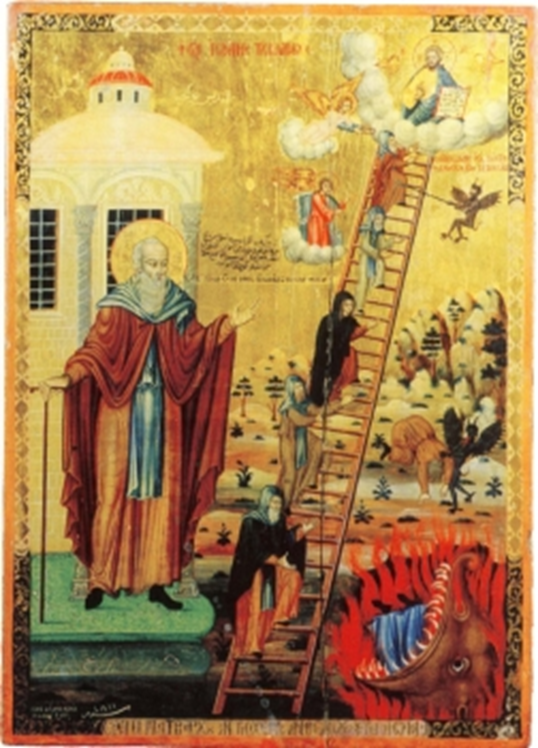

In the book, Everywhere Present, by Stephen Freeman, the central metaphor is the contrast between a “two-storey” and a “one-storey” universe. The “two-storey” view, which Freeman argues is the prevailing mindset in secular society, relegates God and all spiritual matters to an unreachable “upstairs” realm. This effectively banishes God from everyday existence, making faith a distant, theoretical concept. The “one-storey universe,” in contrast, recognizes that God is “everywhere present and filling all things” in the here and now.

This metaphor bears similarity to Stithatos’ contrast between passivity and total engagement, running in circles and ascending upwards.

Freeman’s book advocates for a faith that changes how one perceives and interacts with the entire world and sees God’s presence in all things.

Stithatos’ path to theosis is similarly a transformative process by which a veil is lifted, and we can suddenly see the world around us with new eyes. We are able to discern God’s presence under the surface of even the most insignificant things and, hence, comprehend their true essence.

But true devotion of soul attained through the spiritual knowledge of created things and of their immortal essences is as a tree of life within the spiritual activity of the intellect