STEP 4B

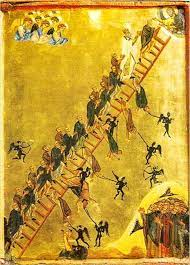

Since Lent has started, we are pausing our studies in Philokalia for a while to re-read the Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus. With the exception of the Bible, writes Bishop Kallistos Ware in the introduction of this book, there is no other book as influential and foundational for Orthodox spirituality as the Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus. It embodies the transformational journey that all Christians are capable of, and have a right to, from the tumult of passions and fragmentation to wholeness, inner stillness and unity with God. We use the edition, translated by Colm Luibheid and Norman Russell. Note, however, that my quotes are from a different, online translation. You can order the book from Amazon.

______________________________________________________________

In step #4, St. John brings up examples of obedience that are jarring to the modern sensibility.

On a visit to a monastery, for example, St. John notices a monk, called Abbacyrus, who is ill-treated and humiliated by all other monks. He has lived in the monastery for 17 years under this obedience. When asked about his apparent sufferings, the monk responds joyfully that he is thankful to God and the other monks for his humiliation and is certain that the goal was to benefit his soul. He explains that during these 17 years, he has never had to battle the demons. The benefit of such state of peace is worth the pain.

John mentions yet another example of extreme obedience. A monk named Macedonius, falsely confesses sins that he had not committed so he can gain humility through his subsequent punishment. When John asks him why he is pursuing such a humiliating course of life, he responds:

Never’, he assured me, ‘have I felt in myself such relief from every conflict and such sweetness of divine light as now. It is the property of angels,’ he continued, ‘not to fall, and even, as some say, it is quite impossible for them to fall. It is the property of men to fall, and to rise again as often as this may happen. But it is the property of devils, and devils alone, not to rise once they have fallen.’

“Blessed is the monk who regards himself as hourly deserving every dishonour and disparagement,” St. John concludes… “He who will not accept a reproof, just or unjust, renounces his own salvation.”

Nothing could be more diametrically opposite to the secular point of view that equates “winning” with success in imposing our will. Our delusion stems from our belief that we make the world (our children, home or workplace) right when we impose on them our sense of order. This belief burdens us with self-imposed responsibility. Instead of experiencing inner stillness we are constantly “on call” – judging, criticizing, maneuvering, controlling and, often conflicting with, others.

John asks us to compare the perceived extremity of total obedience with the extremity of anxiety in lives driven by our will and passions.

This anxiety has become such an intrinsic part of our daily lives that we are barely aware of it. Think about the latent unrest we experience at most moments of our lives, which we have come to perceive as “normal.”

In conversations we can hardly wait for someone of a different view to finish so we can insert our own opinion and set everyone straight. We can’t relax in the act of truly listening because we are silently constructing brilliant responses. We are constantly scanning our environment to ascertain that we and our family are well perceived by others. We are quick to identify and respond to any possible sign of disapproval, disrespect, slander, or injustice against us. We are drowning in activities—kids’ sports, conferences, meetings, social events where we can meet people of influence, opportunities for being visible and influential. Not that any of these things are inherently bad of course. Yet driven by our will and desire to control, such impulses dominate. We can never experience inner peace.

To achieve the goal of stillness of the soul, St. John advises meditation and restraint.

Control your wandering mind in your distracted body. Amidst the actions and movements of your limbs, practise mental quiet (hesychia). And, most paradoxical of all, in the midst of commotion be unmoved in soul. Curb your tongue which rages to leap into arguments. Seventy times seven in the day wrestle with this tyrant… Gag your mind, overbusy with its private concerns, and thoughtlessly prone to criticize and condemn your brother, by the practical means of showing your neighbour all love and sympathy.

Obedience means that you relinquish your role as the ruler of the word, the need to always manipulate, impress, control, come into conflict with others or talk over them to assert yourself or your universe will collapse.

Fix your mind to your soul as to the wood of a cross to be struck like an anvil with blow upon blow of the hammers, to be mocked, abused, ridiculed and wronged, without being in the least crushed or broken, but continuing to be quite calm and immovable. Shed your own will as a garment of shame, and thus stripped of it enter the practice ground. Array yourself in the rarely acquired breastplate of faith, not crushed or wounded by distrust towards your spiritual trainer.