“All that remains,” the last chapter begins, “is the triad of faith, hope and love to be fully united to God.”

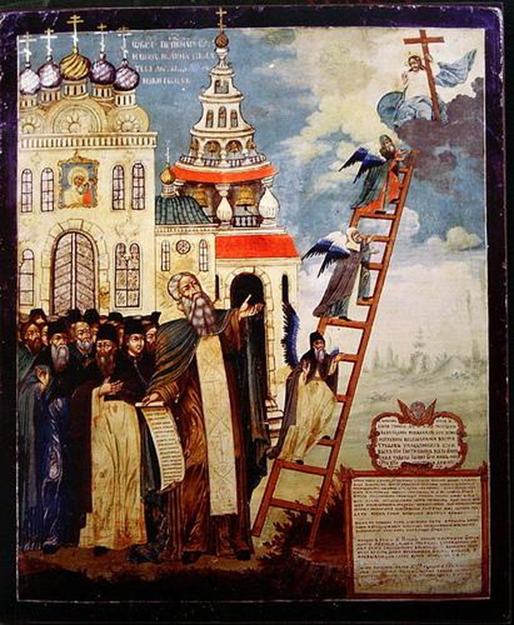

At the 30th and last step of the ladder, we have finally arrived at the summit: theosis or union with God.

When I was younger, I would have expected something rare and powerful at the very top of the Ladder. Infinite wisdom, perhaps; eternal life on earth, immediate sainthood, power over others, miracle-granting authority! Extraordinarily, at the very top of the Ladder is a triad of virtues, with the highest among them being love. Instead of magic powers, we achieve a spiritual state that, though hard, is possible to be achieved by all.

The purpose of all the battles against passions and the cultivation of virtues along our long ascent on the ladder was to finally experience love in its fullness. Since God is love, we become one with Him.

To understand the concept of love in the writings of the desert fathers, we must banish our associations with romantic love or obsessive passion. Christian love is not selective or conditional. It does not ebb and flow with circumstances or mood. Having shed our passions through our ascendance on the ladder, we are free from the blindness of personal agendas, resentments, jealousies, recrimination, desire to control and all the other passions that separate us from God. We are now able to see the image of God in others, regardless of their behavior, flaws, circumstances or mood.

Having achieved the ability to love fully we have not simply acquired a virtue, but become transformed in God’s image:

Love is by its nature resemblance of God, insofar as this is humanly possible.

Achieving theosis is a state beyond words or actions, a true “inebriation of the soul.” When your heart is filled with love, it transforms the way you see and experience the world.

Love grants prophecy, miracles. It is an abyss of illumination, a fountain of fire, bubbling up to inflame the thirsty soul. It is the condition of angels and the progress of eternity. You cannot love God and hate your neighbor because you now see God in him.

You experience love’s “distinctive character,” and thus become “a fountain of faith, an abyss of patience, a sea of humility.” Fear disappears when love consumes you.

Fear shows up when love departs. Lack of fear means that you are either filled with love or dead in spirit, John observes.

A metaphor often used to communicate the intensity of our love for God is that of a person deeply in love. Just as someone besought with erotic love can think of nothing but the object of that love, those who ascend to the top of the ladder are so consumed by divine love that they may forget to eat and are unaware of physical needs.

Yet unlike bodily passions love of God is not uncontrollable, suffocating and destructive. It does not obliterate our identity and sense of self. Christ gave up his life out of love but retained his personhood. Instead of consuming and destroying, love of God transforms.

Hope is the power behind love. When hope goes, so does love. “Hope comes from the experience of the Lord’s gifts, and someone with no such experience must be ever in doubt.” Hope is destroyed by anger.

John’s last admonition is also a glorification:

We are here at the summit,” he reminds us. “Let the ladder teach us the spiritual unity of these virtues so the “grossness of the flesh” will not hold us back. And the chapter ends with an unequivocal declaration.

Remaining now are faith, hope and love, these three. But love is the greatest of them all.” (1 Cor. 13:13)