Philokalia, vol. 4, On the Inner Nature of Things and on the Purification of the Intellect

Dispersed through the austere examples of ascetic practice in Stithatos’ texts, there are abundant references to bright and even ecstatic joy.

Stithatos puts a special emphasis on joy, viewing it not as a fleeting emotion but as a profound, consistent spiritual state and one of the essential “fruits of the Holy Spirit.”

He describes several types of joy. For example:

The joy that stems from the practice of virtues: “When our intelligence is perfected through the practice of the virtues and is elevated through the knowledge and wisdom of the Spirit and by the divine fire, it is assimilated to these heavenly powers through the gifts of God, as by virtue of its purity it draws towards itself the particular characteristic of each of them.”

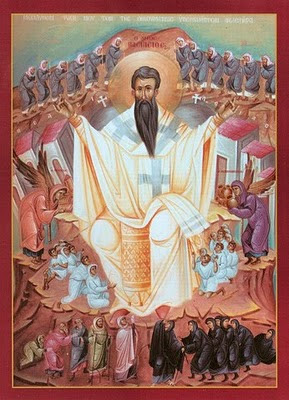

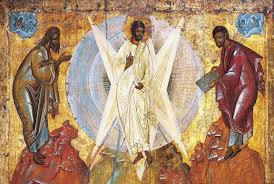

- The joy of dispassion and unity. Shedding our attachments to the material world and its passions is the most essential step in the achievement of theosis. Additionally, Nikitas Stithatos describes a mystical, spiritual reality where the “world above” (the heavenly or noetic realm) awaits its completion and perfection through the spiritual attainment of human beings in the “lower world” (the physical, material world). Instead of being at war with, or separated from, “the world above,” we view it “as yet incomplete.” We understand that the world “awaits its fulfilment from the first-born of Israel…” but we also understand our role in this fulfillment which comes “from those who see God,” and “it receives its completion from those who attain the knowledge of God.”

- Joy found in the liturgical experience and hierarchical, and liturgical account of the nine heavenly powers.

“The nine heavenly powers sing hymns of praise that have a threefold structure, as they stand in threefold rank before the Trinity, in awe celebrating their liturgy and glorifying God. Those who come first – immediately below Him who is the Source and Cause of all things and from whom they take their origin – are the initiators of the hymns and are named thrones, Cherubim and Seraphim.”

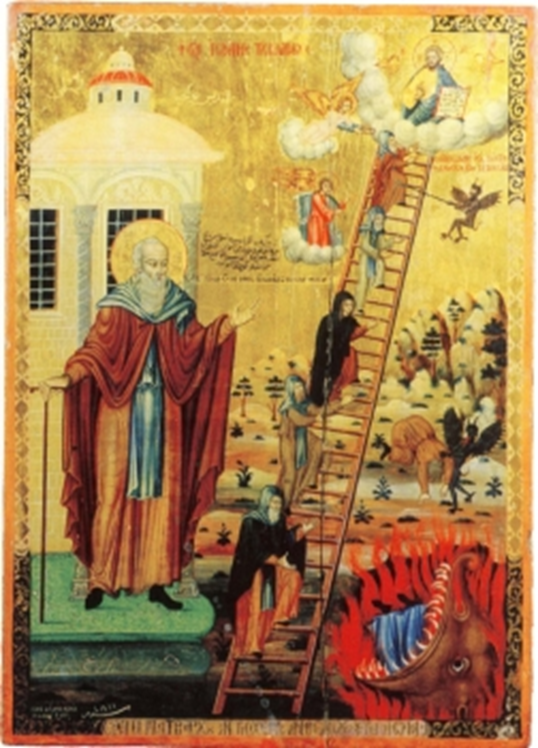

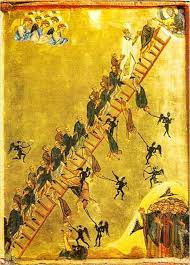

- Theosis: The ultimate joy of inner peace. Joy is an “ineffable” and “incomprehensive happiness” that comes from detachment from worldly passions and the ensuing union with God. This is a core part of the final stage of spiritual life (theosis or deification).

The desire to experience the “joy and sweetness of His presence” is presented as a driving force for achieving inner stillness, emphasizing that despondency is incompatible with the love of God. This state represents the culmination of the spiritual journey.

For those who with the support of the Spirit have entered the fullness of contemplation, a chalice of wine is made ready, and bread from a royal banquet is set before them. A throne is prepared for their repose and silver for their wealth.

- The joy of hope. Even if we do not experience a state of theosis in this life, we should be comforted by the knowledge that the Kingdom of Heaven will open for us after death. Stithatos enters details of the actual physical process of dying and advises us to learn we should ask that our departure from this life may take place without fear.

In summary, for Stithatos, joy is a central, essential element of the mature spiritual life, signifying the soul’s harmonious dwelling in God’s presence.