Nikitas Stithatos

Philokalia, vol. 4, On the Inner Nature of Things and on the Purification of the Intellect:

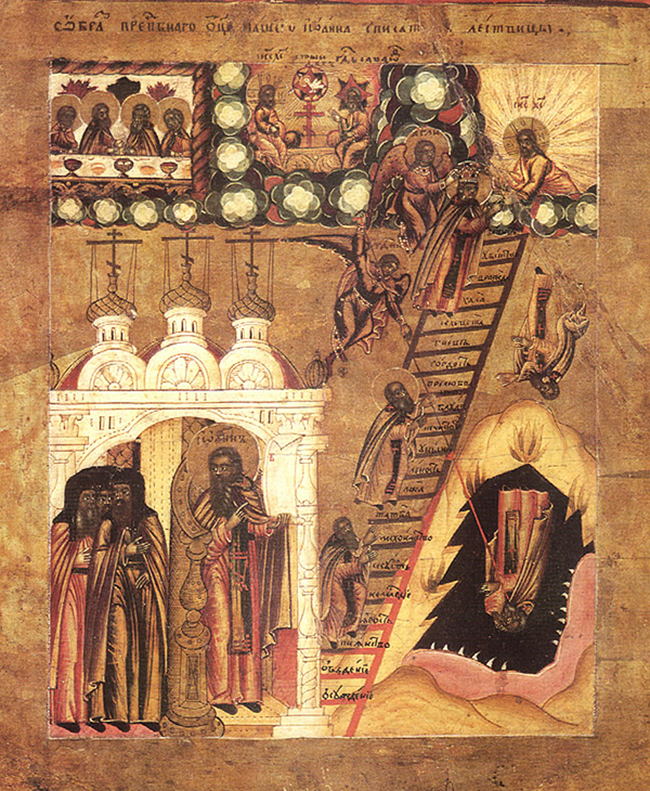

The understanding of dreams serves as an entry point for Stithatos’s broader mystical philosophy of theosis, the gradual process of becoming more like God. This transformation unfolds in three distinct stages: dreams, visions, and revelations.

- Dreams: The First Step of Purification

- There is a direct correlation between who we are and what we dream. If we are attached to material things, for example, we will dream of possessions. If we are addicted to praise and success, we may dream of ourselves in powerful positions, dominating others and being admired.

- A virtuous life produces peaceful dreams. We rise from bed filled with peace, gratitude and the living presence of God

- However, Stithatos notes that even these purified dreams are imperfect. They are produced by the “image-forming faculty of the intellect,” which is mutable and thus unreliable.

2. Visions: Beyond the “Image-Forming Intellect”

- Moving beyond dreams, the soul can experience visions. Unlike the fleeting images of dreams, visions are constant and unchanging, leaving an unforgettable imprint on the intellect.

- These visions reveal future events, inspire the soul with awe and engender a sense of repentance.

3. Revelations: Union with the Divine

- The final, and most advanced, spiritual stage is that of revelations. With a purified and illuminated soul, an individual can transcend ordinary sense perception and understanding.

- It is like a veil has been lifted and we can perceive the true, inner essence of things that lie beneath the surface. We are no longer separated from God, so we are whole and free from struggle, conflict and contradiction. We have advanced beyond words and images to become God-like and perceive His hidden mysteries. Everything now makes sense, and we understand the ultimate purpose of all things, and our own role in God’s creation.

Stillness as the path to Theosis

Those who achieve visions and revelations are no longer troubled by everyday anxieties and concerns. This allows them to achieve a state of inner stillness, which is a prerequisite for theosis.

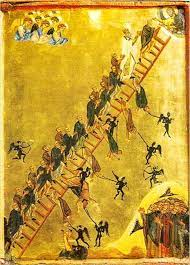

Reaching this state of stillness requires restraint, conquering our will and triumphing over our own impulses. The path of the monk or nun—involving fasting, poverty, and other forms of ascetic discipline — is one example of a complete surrender of the passions. For modern readers, asceticism can seem unrealistic or off-putting, but its core principle is highly relevant: gaining control over our passions and “addictions” rather than being controlled by them, and achiving inner peace.

Without restraint, our will to succeed, possess, indulge, gain status, receive praise and approval, control or defeat drives us.

We use external things to quell our inner fears and anxieties: we abuse substances, become workaholics, become dependent on others’ approval, and chase success at all costs. We sacrifice inner peace and contentment for perceived material success, becoming addicted to external gains and desires.

In this state, Stithatos writes, our true, God-given soul is “disordered” and at war with itself, unable to receive divine grace.

A passionate soul, like a leaf in the wind, is unstable. It is elated by praise and success but devastated by criticism and failure. Stillness is the antithesis of this instability. It is “an undisturbed state of the intellect, the calm of a free and joyful soul.”

In stillness, however, since our contentment is no longer dependent on external factors, we experience an “unwavering stability of the heart in God.”

The Result of Stillness

Freed from the inner battle, our perception becomes clear. We can ascend from contemplating visible things to a profound apprehension of the divine, eventually transcending images, words, and thoughts to achieve complete union with God. The pure intellect, having internalized divine principles, then reflects God’s wisdom, uncovering the deeper mysteries of creation.

Starting with dreams of things visible we ascend to the ever-increasing apprehension of things until we reach beyond images, words and thoughts to become united with God.

When the intellect has interiorized these principles and revelations and made them part of its own nature, then it will elucidate the profundities of the Spirit to all who possess God’s Spirit within themselves, exposing the guile of the demons and expounding the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven.