“Prayer,” John tells us in the beginning of this chapter, “is future gladness, action without end, wellspring of virtues, source of grace, hidden progress, food of the soul, enlightenment of the mind, an axe against despair, hope demonstrated, sorrow done away with.” This stream of lyrical metaphors establishes an important theme: prayer is not a discrete act, strictly confined to a specific place and time. It is nourishment to our souls; the personal experience of God’s presence which can dwell ceaselessly within us.

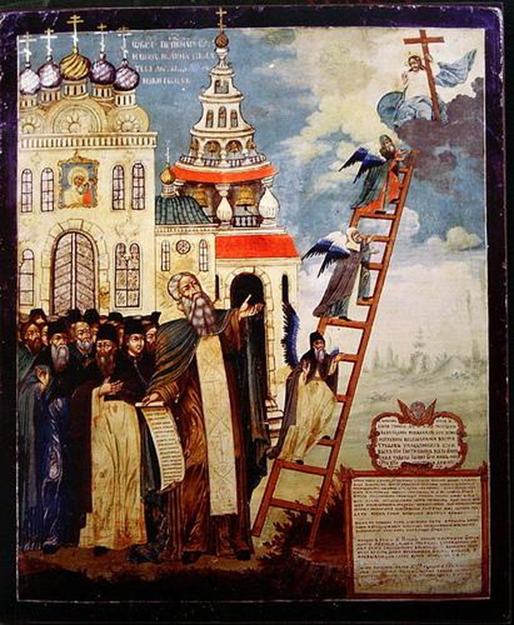

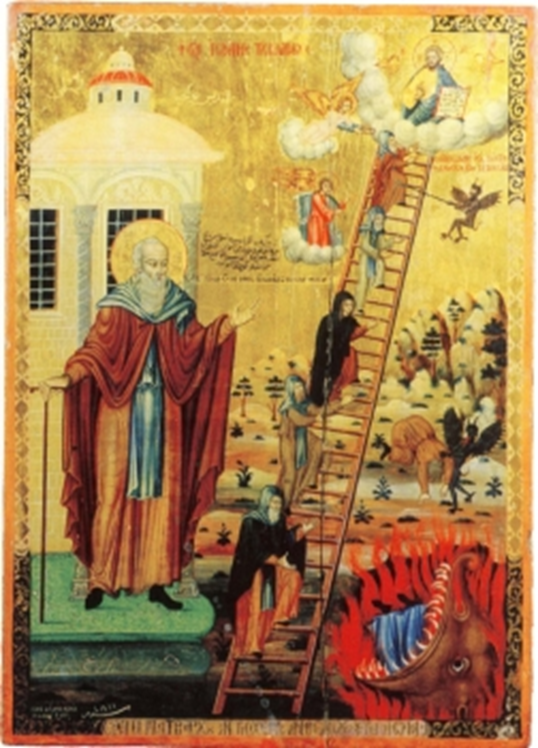

John leads us to gradually deeper stages of prayer from simply keeping physical prayer routines to transforming your entire life into ceaseless prayer.

The first step is to prepare for prayer through purification:

The beginning of prayer is the expulsion of distractions from the very start by a single thought.

Prayer is tarnished when we stand before God, our minds seething with irrelevancies. It disappears when we are led off into useless cares. (p.277)

Distractions from mundane cares and seething passions are likened to imprisonment, keeping us from the shining freedom achieved through prayer.

If you are clothed in gentleness and in freedom from anger, you will find it no trouble to free your mind from captivity (p. 276)

Simplicity and submission are the antidotes to distraction: “Pray in all simplicity,” John tells us. ”Avoid talkativeness lest your search for just the right words distracts you.” In fact, “when a man has found the Lord, he no longer has to use words when he is praying …”

You truly pray when you ask for understanding of His and submerge your ego to it. “While we are still in prison, let us listen to him who told Peter to put on the garment of obedience, to shed his own wishes and, having been stripped of them, to come close to the Lord in prayer, seeking only His will.

The Fire that Resurrects Prayer

It is easy to forget that prayer is a gate to the presence of God and begin to see our daily prayer rituals as chores or even disruptions to our busy lives. John reminds us that prayer is not an opportunity to make requests but a reward unto itself as a vehicle for uniting with God.

“What have I longed on earth besides you? Nothing except to cling always to you in undistracted prayer!”

The stage of unity of God is not one of passive submission but of spiritual transformation. John uses the metaphor of fire to describe it: “When fire comes to dwell in the heart,” he says, “it resurrects prayer.”

Such an ecstatic state is not achieved on demand. We live in a time when service or information on demand, anytime, anywhere, is considered our birthright and the natural course of events. Yet, reaching this mystical, prayerful state cannot be achieved through our own efforts and at our chosen time, but only through God’s Grace. This is why when, by God’s Grace, our souls are suddenly gifted with a moment of true prayer, we must not let anything interfere with it. “Do not stop praying as long as, by God’s grace, the fire and the water have not been exhausted (as long as fervor and tears remain), for it may happen that never again in your whole life will you have such a chance to ask for the forgiveness of your sins.”

One of the greatest dangers in our time is to look for shortcuts to ecstatic communion with God, replacing the fire of God’s presence in prayer with the superficial “high” of excess or addiction—whether it is drugs, extreme sports, workaholism or other compulsion. The danger for us, practicing Christians, is to transfer this attitude to our prayer life, seeking “highs” in our prayer and worship experiences and judging their quality of the basis of the emotions we believe we should be feeling. Forcing the emotions we think we should be feeling in worship and judging rather than submitting to prayer and worship—leads some to constantly “shop” around for churches or for rapturous worship experiences which, ironically, does not give them the inner stillness needed to truly pray.

We shouldn’t confuse the fire that is stoked by the labor of ascending the Ladder and emptying ourselves from passions, with artificially induced emotions. The fire that comes to dwell in the heart and engenders true prayer is achieved through the Grace of God rather than our will and through spiritual warfare. Above all it transforms rather than to simply excite or entertain us.

Prayer as Transformation

John places a great deal of weight on the transformative role of prayer. He considers those who emerge from prayer without having experienced [illumination, joy or peace] to have prayed bodily rather than spiritually. “A body changes in its activity as a result of contact with another body. How therefore could there be no change in someone who with innocent hands has touched the Body of God?”

John, however, is a pragmatist and wants us to at least adhere to the discipline of prayer routines, even when our hearts are closed and are not participating in the prayer. Committing to these routines eventually allows our hearts to follow our bodies.

For those who have achieved the higher level of true prayer, prayer is no longer a distinct activity but a continuous spiritual state.

John tells us that we should aspire to this state of continuous prayers. In is living life as prayer than our lives are transformed. We experience life—even its most insignificant moments or mundane elements —as “as sacrament” (as Schmemann puts it). Life is lived as whole; there is separation between sacred and secular; worldly and prayer life. We may have a set time for prayer, but we are already prepared for it by “unceasing prayer in [the] soul.”