Taking a short break from St. Maximos and switching to Staredz Silouan is like  leaving the turbulent, vast ocean to rest for a while on a calm, translucent lake.

leaving the turbulent, vast ocean to rest for a while on a calm, translucent lake.

Metaphors, complex series of paradoxes, parallelisms and allusions are sparse; the narrative is direct and experiential.

What does it mean to “know God” and how important it is to our relationship with Him, asks Silouan in this chapter?

To respond, he first makes an essential distinction between seeing and understanding beyond what is visible:

…a multitude of people beheld the Lord in the flesh but not all knew him as God.

Even believing in God is not the same as knowing, he states: “To believe in a God is one thing, “to know God another.” He continues further down: “Many philosophers and scholars have arrived at a belief in the existence of God, but they have not come to know God.”

God wants us to know Him. “The Lord loves man and has revealed himself to man.” Yet it is impossible to recognize what is being revealed since we can only understand what we can discover through our senses, intelligence, educational experience and even by the force of our belief. Going beyond human capabilities requires the help of the Holy Spirit.

Both in heaven and on earth the Lord is made known only by the Holy Spirit and not through ordinary learning.

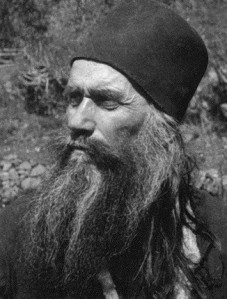

Silouan states his thesis and goals clearly at the very start of the chapter. He tells us that, though a sinner, he has come to know God through the Holy spirit. He now wants to share what he has learned so “that others might come to know God and turn to Him.”

Most importantly, Silouan wants us to understand what the Holy Spirit does for us. Without the Holy Spirit, we would be limited to what we can see on the surface or understand through the narrow limits of our human capacity for learning. We would thus be able to increase our knowledge in a linear fashion—accumulating facts, exposing ourselves to new ideas or carrying on clever conversations — yet without increasing our capacity to know God. We would be still stuck in the world that we, as humans, are capable of perceiving and understanding. The Holy Spirit stretches us beyond ourselves and human capabilities.

The Holy Spirit unfolded to us not only the things of the earth but those too which are of heaven.

Without the Holy Spirit, we could not know God “…for how can a man think on and consider a thing that he has not seen or heard tell of and consider a thing that he has not seen or heard tell of and does know?”

With the Holy Spirit dwelling in us, we are no longer subject to the laws of the flesh and will see our fears evaporate as did the Apostles and the prophets. Silouan quotes St. Andrews, saying:

If I feared the Cross, I should not be preaching about the Cross

Instead, of delivering increased knowledge, the Holy Spirit allows us to glimpse into the perfect love of God, thus, enabling us to know Him and transform our entire perception of, and relationships with, the world around us.

The lord is love…and the Holy Spirit teaches us this love

The greater our love for God, St. Silouan tells us, the more complete our understanding of His sufferings and, hence, our knowledge of Him.

The Holy spirit does not mechanically settle into our souls. We have to enter into a living and personal relationship with Him. Without a relationship with the Holy Spirit, we are left acting as our own authority and fashioning a narrow world that fits our own limited perception of needs.

…but people want to live after their own fashion and consequently they declare that God is not, and in so doing they establish that He is.

Conversely, by the grace of the Holy Spirit, we are free of material limitations and expand to participate in, not just learn about, God

…The man who knows the Lord through the Holy Spirit becomes like unto the Lord. He quotes St. John the Divine: “We shall be like him; for we shall see him as he is. And we shall behold his glory.

Vice, Fourth Century, #78-89

Vice, Fourth Century, #78-89 that there was a disconnect somewhere between your own stories about yourself and your actual experience of who you are?

that there was a disconnect somewhere between your own stories about yourself and your actual experience of who you are? Virtue and Vice, Fourth Century, #51-63

Virtue and Vice, Fourth Century, #51-63 Vice, Fourth Century, #40-50

Vice, Fourth Century, #40-50 After the fall, St. Maximos tells us, our human nature became impassioned. This was because we distorted and redirected the true longing for God that He implanted in our nature, and our capacity for experiencing pleasure in his presence.

After the fall, St. Maximos tells us, our human nature became impassioned. This was because we distorted and redirected the true longing for God that He implanted in our nature, and our capacity for experiencing pleasure in his presence. Virtue and Vice, Fourth Century, #26-33

Virtue and Vice, Fourth Century, #26-33 To grasp the complex paths to salvation that St. Maximos lays out in these paragraphs, we must first understand that human nature is inherently good rather than a synonym for passions and abandonment. St. Maximus tells us that “sin is what is contrary to nature” and that what “is beyond nature is the divine and inconceivable pleasure which God naturally produces in those found worthy of being united with Him through grace.”

To grasp the complex paths to salvation that St. Maximos lays out in these paragraphs, we must first understand that human nature is inherently good rather than a synonym for passions and abandonment. St. Maximus tells us that “sin is what is contrary to nature” and that what “is beyond nature is the divine and inconceivable pleasure which God naturally produces in those found worthy of being united with Him through grace.” St. Maximos delves once more into the intricacies of the relationship between soul and flesh. He reminds us that his is not a doctrine of separation and polarization between God-given faculties. To nourish the soul, you do not need to annihilate the flesh. You need to understand and follow the correct order.

St. Maximos delves once more into the intricacies of the relationship between soul and flesh. He reminds us that his is not a doctrine of separation and polarization between God-given faculties. To nourish the soul, you do not need to annihilate the flesh. You need to understand and follow the correct order. experience, rather than hardship. Years later, I switched to automatic transmission, which I found much easier. I wasn’t exactly full of gratitude for this improvement. Instead, my perception of what was normal had rapidly changed, so that automatic transmission was now an expectation. Now heated seats, keyless entry and built-in GPS are my new normal. I hate to admit it but I would probably seize on the next innovation, whether it was flying cars or transmuting myself into atoms that could be reconfigured back into my person in another location, within seconds–like Dr. Spock and the rest of the Star Trek characters.

experience, rather than hardship. Years later, I switched to automatic transmission, which I found much easier. I wasn’t exactly full of gratitude for this improvement. Instead, my perception of what was normal had rapidly changed, so that automatic transmission was now an expectation. Now heated seats, keyless entry and built-in GPS are my new normal. I hate to admit it but I would probably seize on the next innovation, whether it was flying cars or transmuting myself into atoms that could be reconfigured back into my person in another location, within seconds–like Dr. Spock and the rest of the Star Trek characters.